How Grassroots Organizations Are Fighting Food Insecurity, One Meal at a Time

Los Angeles is a city of creative dreams and cinematic productions. It’s a place where starry-eyed people flock, and which exports culture-defining stories to the world.

Stories, though, aren’t L.A.’s only export. When it comes to sheer volume and impact, food might be on equal footing. L.A. County is the second-biggest exporter of food in the United States, contributing 6.5 billion pounds to the country’s food system each year, with a crop value of more than $177.5 million. L.A. imports food, too: At seven billion pounds, it’s the third-largest importer in the U.S.

Yet, despite this literal cornucopia, as of August 2023, one in four households in the county – one million households total – experienced food insecurity. That’s an uptick of 6% since last year, according to a recent report from the University of Southern California, and the highest rate of county-wide food insecurity since 2010. Of those, Black and Latinos are more than twice as likely than white residents to experience food insecurity, says Kayla de la Haye, who directs USC’s Institute for Food System Equity.

There are a myriad of forces that, collectively, cause and exacerbate food insecurity. Among them are poverty, fear of legal repercussions – which can be particularly true for undocumented immigrants – as well as language barriers, and access to childcare. Food insecurity isn’t just about quantity, but also quality.

Food deserts – where affordable, high-quality food is farther than walking distance – are places where that access is even tougher. In Los Angeles, for example, South L.A. has long been a food desert where multiple factors, from economics to distance, make finding high-nutrition food a challenge. A lack of both quantity and quality compounds the problem and can trigger a cascade of health issues, especially for children.

“The consequences of this can really set these kids on to poor trajectories for their health and their well-being in the long run,” said De la Haye, in an interview with LAist. “They may have more trouble concentrating, more risk for anxiety.”

It was that question of quality, in fact, that in 2017 prompted Jamiah Hargins, the founder of nonprofit Crop Swap, to plant his first vegetable garden. He was traveling often for work and expecting his first child when he began to notice that eating on the road didn’t have much in the way of health benefits. He started imagining having to feed his daughter that way, too. Gazing at his backyard one day, his home-grown idea took root.

But what began as a project to feed his family well soon blossomed into something much bigger. Within a few months of planting his garden, Hargins had more produce than he could eat, so he invited green-thumbed neighbors to swap surplus crops. The meetup was a success, and prompted him to launch, briefly, a local farmers market. But a turning point came in 2020. That year, he won a grant from LA2050, an organization aimed at making social change in the city.

“The idea was to take over front yards of homes and do our best to grow food,” said Hargins. “I didn’t even have a business plan at that point.”

Yet, the project flourished – literally. With the grant money, an agricultural mentor and a team of volunteers, Hargins launched Asante Microfarm, a member-based farm in View Park, Los Angeles. For $60 each month, residents living within one mile of the front-yard farm could get weekly bags of fresh produce. Sustainability and community are built into Asante’s ethos, starting with the no-drop-wasted approach to water conservation and extending to the low carbon impact of local food pickups.

Today, Asante is one of three farms in the Crop Swap organization, which collectively employs 17 people, feeds 70 families (215 people) each week, and has a fourth farm in the works. While the produce helps close the access gap in the neighborhoods they serve, the role the farms play goes far beyond food – encompassing culture, community, and economics.

For Hargins, the first impact of this work is his presence. “The fact that this is a Black neighborhood [where I live], a lot of folks didn’t expect a new homeowner here to be a young Black man,” he said. Being a leader who looks like his neighbors, he said, has been powerful.

The next is economic – $60 for a month’s worth of high-quality produce, especially in L.A., is a bargain. Finally, the farms have become community hubs for the urban farmers and neighborhoods alike. In addition to the memberships, Crop Swap hosts gardening workshops, school events, and garden installations.

“People feel like there’s a sense of love and ease and kindness in our spaces,” said Hargins. “Volunteers consistently show up for years. Yesterday two people in Leimert Park asked me for a job within an hour. We’re showing that there’s power in kindness.”

The data backs up Hargins’s experience. The Larta Institute, a think tank on food equity, pointed to the power of the practice as a source of community resilience, economic savings and opportunity, as well as sustainability. A 2023 report they issued with the Los Angeles Food Policy Council underscored that halo effect:

“Urban growers respond to their community’s desire for quality food and engage with their neighbors to develop trust. Knowledge sharing has fostered networks… [that] facilitate grant applications, resource sharing, creative implementation, and assistance with permitting processes.”

Growing food is a multifaceted tool to combat food insecurity. But for Othón Nolasco and Damián Diaz, providing meals for L.A. families started not in the yard, but the restaurant kitchen.

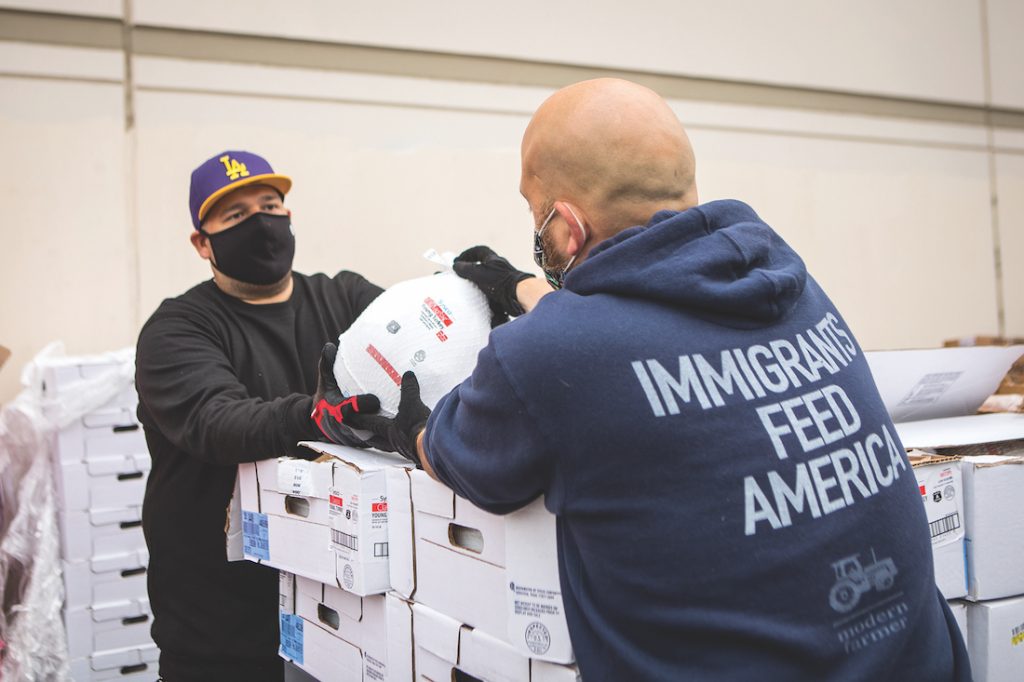

In March 2020, they had just hired a staff of front- and back-of-house workers to open a new dining venue when establishments across the city shut down due to COVID. The two were longtime bartenders and much of their staff were undocumented immigrants, without access to unemployment funds or government aid. As service workers’ income city-wide came to a halt, the pair decided to give groceries to their staff for a few weeks, with an eye to helping their friends in the short-term.

Soon, though, word spread. It wasn’t long before they were feeding more people than they could reasonably afford. Within a few months, they became a 501c3 called No Us Without You (NUWYLA), and began to secure grant money to meet the growing need. At its height, the organization served 1,700 families, said Nolasco. More recently, that number has dropped to 600 – not because the need had faded, but because, post-pandemic, donations shifted. He and Diaz have a waiting list at the ready.

But food insecurity, they know, didn’t start with the global pandemic, and it didn’t end with it, either. While many of the families they serve have been able to return to work, restaurants aren’t open as long as they were before 2020; in turn, workers’ hours are often cut. And, the savings that families used up during that time, combined with debts they acquired – to pay things like rent, phone bills, or school supplies – are still taking a toll. Nolasco knows families whose children might do their homework parked outside a McDonald’s to access the WiFi; others who might miss a grocery pickup because they sold their car to fund their rent.

“I think people in our program, if they could, would just be back to normal and not have any debt and not get food from our program,” said Nolasco. “That would be their main goal.”

Still, NUWYLA has been a lifeline for many – from a displaced Ukrainian family on the West Side to an elderly woman on the East. Because of its community reach and trust, people who might fear interacting with the government, or face technical barriers, bureaucratic hurdles or language issues, among other things, are receiving essential services that they might not otherwise get. Even for those who can navigate getting government services, said Nolasco, the eligibility requirements can be narrow and the benefits short-lived.

“Women and children’s [WIC] is great,” he said. “But you only qualify for so long and so much.” In contrast, NUWYLA has “built rapport with families in need, and everything’s been word of mouth.”

Much of that rapport has come as a result of Díaz’s outreach. He gives families his phone number, and keeps detailed spreadsheets of every participant and every need, beyond food alone. Last year, he said, a participant who had saved up to buy a toolkit for work was devastated when it was stolen from his truck. Díaz put the word out to the NUWYLA network and within weeks, the participant had been gifted a new set, all through donations.

“This is the type of work that we’re doing,” said Díaz. “It starts with a box of food but it ends with whatever needs to be met.

“We’re not here to be a welfare,” he continued. “We’re not here to enable people. We’re here to get folks where they need to be financially, spiritually, and physically.”