New Money

Philanthropy, incorporated for the public good, can and should make all its investments accordingly.

In 2021, Senators Angus King (I-Maine) and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) introduced a bill to more tightly regulate donor-advised funds, commonly referred to as DAFs. While the Accelerating Charitable Giving (ACE) Act’s reforms were far from sweeping, the bill set off a bitter debate over who controls charitable funds: the donor or the public.

The Act’s supporters plausibly argued that wealthy donors could use the increasingly popular philanthropic instruments for personal gain, and that DAFs allow them to hoard and perpetually control what becomes public money once those donors accept a tax benefit.

Its detractors plausibly argued that the bill would reduce charitable donations by constraining donors’ access to an easy way to commit large sums to charity, even if the gifts to nonprofits don’t happen immediately.

For the uninitiated, DAFs are like charitable bank accounts that allow a donor to make a “donation” of money or complex assets. The primary sponsors of these accounts are increasingly subsidiaries of large investment firms – like Fidelity, Schwab, and Vanguard – and community foundations. The donor receives a tax deduction for the year that the gift was made but isn’t compelled to disburse those funds immediately.

“We want to make the timing of the deduction and the benefit to the community closer together than the current sometime from today until infinity,” says Jan Masaoka, the longtime CEO of the California Association of Nonprofits, which supports the ACE Act.

The bill, which hasn’t moved to a vote in the Senate, but was introduced in the House in early 2022, targets the estimated $160 billion DAF industry. Most importantly, it would compel donors to spend down those accounts within 15 years or submit to 5% annual payouts if they want to retain control for 50 years.

One of the bill’s most strident opponents is the Philanthropy Roundtable, a national association of similarly-minded charitable foundations.

“Our mission is to help foster excellence in philanthropy, to protect philanthropic freedom, and to help donors advance the principles of liberty, opportunity, and personal responsibility,” says Elizabeth McGuigan, the Roundtable’s senior director of policy and government affairs. “This entire legislation is aimed at hypothetical problems. What we see is robust giving coming out of donor-advised funds… The best way forward is to protect philanthropic freedom and donor privacy, which of course, the ACE Act would violate in many ways.”

She has a point. Private foundations are compelled by federal law to give 5% of the value of their endowments out in grants every year. In aggregate they hew very closely to this number. The National Philanthropic Trust, a DAF sponsor itself, found, through its robust annual survey, that the 2020 payout rate for DAFs nation-wide was 23.8%.

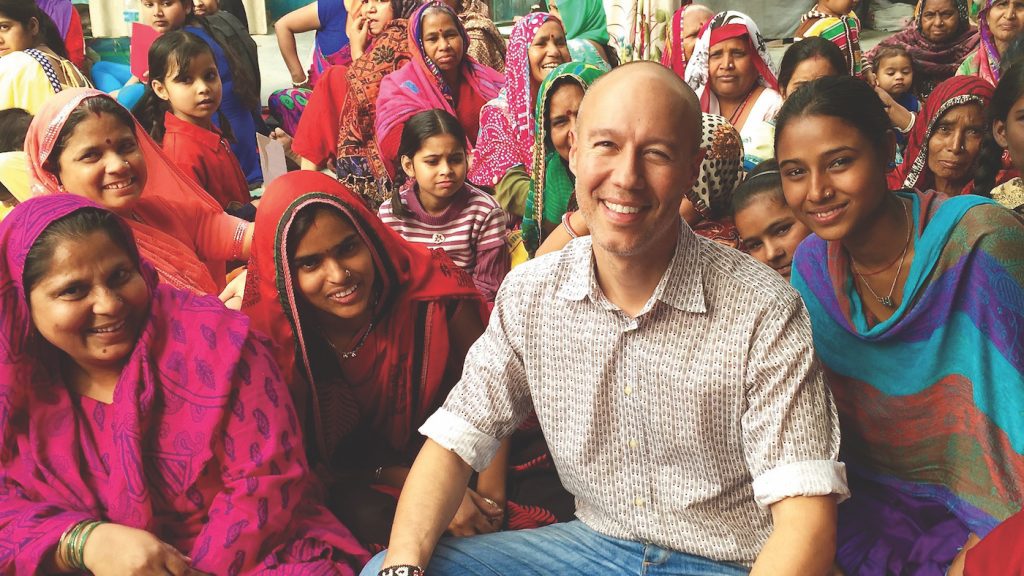

For David Risher, who, alongside wife Jennifer, has inspired more than $33 million in giving through their grassroots #HalfMyDAF campaign, moving the massive wealth locked up in DAFs and charitable foundations requires an “all and” approach.

“Legislation is a pretty big hammer. But if that’s what the world needs, let’s do it,” Risher says. “But meanwhile let’s not wait for regulations to tell us what the right thing to do is. Let’s get to it. Let’s inject some entrepreneurial spirit into philanthropy. That isn’t going to come from the government. It’s going to come from people like you and me and someone like MacKenzie Scott waking up and saying, ‘Let’stry some different things here.’”

More than the substance of the bill itself, the ACE Act’s introduction showed that two senior senators were willing to question whether the tax benefit conferred to donors by the federal government was being matched by sufficient public benefit.

And the government, working on the public’s behalf, is fully entitled to ask these questions. I would argue that it is also every individual American’s responsibility to ask whether philanthropy is living up to its purpose. After all, the donor’s acceptance of tax abatement by setting up a charitable foundation or a DAF creates a legal trust wherein the trustee is the public – you and me.

Despite all the control that the philanthropic sector wields over its assets, it really is the people’s money.

In that context, we should be looking at how capital flows through the true seat of wealth in private foundations – their endowments: the corpora.

The corpora refers to the more than $1 trillion held by charitable foundations in the United States. Remember, this collective of bodies is governed by an Internal Revenue Service rule that compels 5% of its totality be given to charity every year. The rest, the 95%, is largely invested on the private market.

Of the $485 billion that Americans gave out in 2021, charitable foundations made up less than 20% at $90 billion. As this makes clear, the real money lies in foundation endowments and – for individuals – within DAFs housed at the globe’s most successful investment banks.

So how is all that money, owned by the public, being spent? How should it be spent? And what can be done to accelerate investments that support, rather than degrade, this nation’s social safety net and the globe’s ailing environment?

Spending Down

Given the flood of issues affecting us – a teetering economy, an assault on reproductive rights, commonplace mass shootings, a West that burns – maybe it’s best to just spend the money held up in charitable foundation endowments or donor-advised funds as quickly as possible.

That was the tack Kathy Kwan took when deciding the fate of her and her husband’s $60 million Eustace-Kwan Family Foundation. “If all those dollars are locked up in savings accounts, they’re not going through the economy,” Kwan told me. “They’re not helping people.”

By the end of 2023 the total endowment will be spent down. Kwan isn’t alone.

In 2014, after the death of longtime Schwab COO Larry Stupski, wife Joyce declared that the foundation would “spend down” all its assets by 2029. “Spending down gives our team of staff and grantee-partners the opportunity to dream big, take risks, and make real change in our communities,” she said before her death in 2021.

Stupski and Eustace-Kwan are part of a growing roster of foundations that have pledged to give all their money away sooner than the “perpetuity” the majority seek, which I will describe shortly.

Mr. #HalfMyDaf, David Risher, has a similar take, but applied to donor-advised funds. Under the model that he and his wife created, anyone who commits to spending down half his or her DAF within a year is eligible to nominate nonprofits for matching gifts. These can be made by the cadre of DAF holders that have pledged to be HalfMyDaffers, or anyone who visits the website.

Since 2020, #HalfMyDAF has moved an average of $11 million a year, a little more in annual giving than a charitable foundation with a $200 million endowment would give according to the 5% rule.

But spending down means stamping an expiration date on the golden goose.

Perpetuity and Not Terrible Investments

Charitable foundations and the firms managing DAFs, while not uniform in their investment strategies, have one key similarity: an unswerving focus on returns.

Foundations are fond of the concept “perpetuity,” wherein sage fiscal management renders the corpus immortal. To achieve perpetuity, private foundation investments must produce more revenue than their operating costs, which includes the 5% payout requirement. This requires a returns-oriented mindset, which can run counter to the public interest.

While some DAF holders may direct their sponsoring organizations to spend down the money quickly, DAF sponsor fees are derived from the size of the assets managed. This creates a clear disincentive for managers to counsel their clients to give the money away. And while that money sits, the goal is, again, profit.

Fossil fuels can be a very good investment. So too private prisons and firearms. And investments with private equity firms that gobble up distressed apartment buildings and homes and convert them into market-rate rentals can also be lucrative.

But where is the public benefit in any of these?

Recognizing this incongruity with foundations’ missions, an increasing number have joined the now $40-plus trillion Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) industry. ESG simply means that investments in socially and environmentally unappetizing companies and funds are identified and screened out. So, if you are a charitable foundation focused on climate change, your ESG screen will keep you from buying ExxonMobil stock.

That’s a start.

Using the Balance Sheet

When a rich kid wants to buy a home, his or her parents can either purchase or engender a modicum of self-reliance by putting up a loan guarantee to smooth the mortgage over with a bank.

Similarly, charitable foundations can use the power of their balance sheets to offer unfunded loan guarantees to spur private investments in things like solar panel expansion or urban redevelopment.

The Community Investment Guarantee Pool (CIGP), launched in 2019, has pulled together major names in philanthropy and impact investing – the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Arnold Ventures, the Annie E. Casey and Kresge foundations, among others – to offer loan guarantees for a range of socially-conscious private enterprises.

In 2021, the pool used $15 million in guarantees to leverage $131 million in capital to develop affordable housing.

“Affordable housing is an important new issue area for Arnold Ventures,” said Arnold Ventures Director of New Programs Chris Hensman in a 2022 CIGP press release. “We’re excited to participate in the Pool and explore financial guarantees as a highly leverageable tool for helping to launch, test, and scale the most promising of these housing strategies.”

Better.

Patient Capital

In 1969, when Congress passed the Tax Reform Act – which included that 5% payout rule for private foundations – it also created something called a program-related investment (PRI).

Pioneered and lobbied by the Ford Foundation, which has allocated more than $600 million to PRIs, these are investments, most often structured as low interest debt, that fulfill a foundation’s mission.

Per IRS rules, making a profit cannot be the “primary concern” of a PRI. In exchange for accepting concessionary returns, the IRS allows a foundation to count these investments towards their annual payout.

This financial instrument has largely been deployed as “patient capital,” in the form of low-yield loans (1-3% over 5-10 years).

In 2015, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the JPMorgan Chase Foundation launched the Entrepreneurs of Color Fund in Detroit. Since, it has loaned out more than $10 million and helped create and retain 1,100 jobs.

But PRIs don’t need to be structured as loans – they can also be used to buy equity. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has deployed more than $1.5 billion in PRIs. To develop new vaccines, the foundation made equity investments into biotech startups, while compelling those companies to make their products affordable in poor countries.

That’s promising.

Market Rate Returns Meet Social Impact

In 2017, the California Wellness Foundation, which holds a little north of $1 billion in assets, began experimenting with mission-related investments (MRIs). In essence, MRIs are a fancy way of saying market-rate investments that also generate positive social impacts.

“We started with $50 million and set up a mini-endowment with very similar asset allocations to our larger portfolio, and tracked performance,” says Wellness’ chief financial officer, Rochelle Witharana. “We were able to prove that the MRIs tracked exactly the same as the broader portfolio.”

With a flourish Witharana adds, “We are now moving our entire billion to impact.”

Despite increasing evidence that investments can yield acceptable returns with acceptable risk, mission-related investing is far from the norm. The Global Impact Investing Network estimates that while growing, there is only around $715 billion in impact-investing dollars under management globally. For scale, U.S. pension funds alone hold roughly $40 trillion.

The reason why philanthropy has been slow to step up, Witharana says, “is the old boy network [of foundation finance committees and staff]” who “believe that MRIs can’t make the same returns as traditional portfolios, which I feel is completely incorrect.”

The Ford Foundation’s $1 billion Mission Investments program, launched in 2017, is showing that returns can not only exceed expectations, but can also feed the vaunted immortality of a foundation’s corpus.

“Mission Investments has generated a compound annual return rate of 28% from its inception in 2017 through 2021,” Ford President Darren Walker wrote in a 2022 reflection on the program’s five-year anniversary. “That’s triple the return required to sustain the foundation’s perpetual existence.”

While Ford’s MRI carve out is significant, it is far from shifting the whole $16 billion endowment towards double bottom line investing.

There are only a handful of foundations across the country that have done that. In California, I know of only two large foundations, other than Wellness, that have pledged to move their entire endowment to impact: the Weingart Foundation and the East Bay Community Foundation.

Valerie Red-Horse Mohl is the East Bay Community Foundation’s CFO. Among many accomplishments in the world of finance, Red-Horse Mohl founded the first Native American owned investment bank in the 1990s. She came to the East Bay Community Foundation in 2020 to not only change how it invests, but how philanthropy does as a whole.

“I think the way to make reparations is to allow us [Black and Native American People] to thrive and catch up in the wealth gap,” Red-Horse Mohl says. “For me, it’s not so much looking back, even though that’s important. It’s looking forward and how do we really narrow, if not eliminate, the wealth gap?”

Part of that is investing in Black and Brown financial managers, long excluded from the upper echelons of finance. “What happens when money comes into Black and Brown funds from Wall Street?” she asks. “It starts to then flow into companies that are all over America in communities of color. And then we raise the level of wealth in those communities and then the need for all the philanthropic support starts to lessen.”

Cynthia Muller is the director of mission investment at the $8 billion, Michigan-Based W.K. Kellogg Foundation. In 2007, the Kellogg Foundation was one of the first major national foundations to commit to MRIs and has deployed more than $300 million since.

Being so early in, Muller says, Kellogg could set the table on diversity, equity, and inclusion, by making investments that “don’t hurt the underlying communities, but sway markets and practice. When the Kellogg Foundation comes in, it makes it okay for others to come in.”

But don’t get too caught up on the good that mission-related investing can do; market rate returns are the top criteria when investment officers like Witharana, Red-Horse Mohl, or Muller are considering an allocation.

Inasmuch, labeling these investments mission related may be too limiting. If we go back to the original premise of this essay, and accept that all these dollars are truly public, there is an argument to be made that all investments should be mission related.

But instead of compelling charitable foundations to align their investments, can the government incentivize philanthropy to increase momentum towards impact investing?

Changing the Energy of Money

Since the creation of the PRI more than 50 years ago, the practice has become increasingly commonplace across philanthropy.

“In 2022, you can’t go to a foundation or family office without talking about a PRI,” Kellogg’s Muller says.

Community foundations are also taking a leadership role in directing their DAF holders towards program-related investments. The California Community Foundation, through its Home L.A. Loan Fund, has guaranteed returns for DAF clients who have in turn given out more than $11 million in low-yield loans to support affordable housing developments. And the East Bay Community Foundation regularly holds pitch sessions where social entrepreneurs take their ideas to the foundation’s DAF clients directly in the hopes of winning a PRI.

This is evidence that offering philanthropy an incentive can yield sector-wide change. But PRIs are still, most often, part of the 5%. How can we go bigger, move the 95%, the great corpora, to impact?

While the ACE Act uses a stick, albeit small, the federal government also can offer some carrots.

One is the excise tax. Currently, charitable foundations pay 1.39% of net gains on their investments in a calendar year.

The federal government could create any number of incentives for foundations by waiving the tax if, for example, a foundation’s portfolio used an ESG screen or reached a minimum threshold of verifiable MRIs.

Another area for reform could be unrelated business taxable income (UBTI). If a nonprofit, including a charitable foundation, generates revenue from business activities that differ significantly from its mission, it can be taxed at the corporate or trust rate. This can create tax exposure for foundations or DAFs that invest in, for example, real estate funds with debt financing.

If a foundation focused on, for example, alleviating poverty, invests in a market-rate affordable housing fund, it can still be taxed on some portion of the return. The IRS could waive UBTI.

While both the excise tax and UBTI are relatively small expenses, waiving these taxes would show the federal government is supportive of the idea of impact investing.

For Debbie La Franchi, who founded impact investing firm SDS Capital Group more than two decades ago, the real reason why foundations have been slow to impact is more about themselves than federal regulation.

“Our experience with MRIs is either that foundations don’t have them, or they are very narrow, or they want to wait until you are on fund three or four when we don’t need the foundation money anyway,” La Franchi says. “We need the money when we are launching a new concept, especially when it also has an impact.”

Part of the problem, as I mentioned above, is the whole notion of calling out impact investments as mission related. Whether it’s La Franchi’s California-based homeless supportive housing fund, or her fund in the U.S. South, both lead with market-rate returns. Same too for a venture fund that invests in early stage solar, wind, and energy storage companies.

By labeling investments – that could come out of any asset class – as mission related, philanthropy is curtailing the full power of its corpus. Instead of a carve out, they should use their full endowments to build up the field of impact managers, who will create products with the scale and track record to draw institutional money. Remember, pension funds hold about 40 times the wealth that U.S. charitable foundations do.

Government can help through tax policy and other financial instruments, but philanthropy doesn’t need to wait to act.

So, to my friends on the financial side of the philanthropic house, what are you going to do with that $1 trillion ball of our public money in your hands? Will you seek perpetuity through traditional means, or will you find immortality by changing markets, the energy of money?

Now that would be transformational.