A California Gem Hiding in Plain Sight

Andy Candelaria was so determined to go to California State University, Northridge that as a freshman, he commuted for two hours by metro and bus from his home in Downey. Now a fifth-year senior majoring in Computer Information Technology, he lives closer and, thanks to internships facilitated by CSUN, he’s on track for a career in IT security.

Milen Coronado, a fourth-year senior who plans to be a public-school teacher, is a double major in Liberal Studies and Chicana/o Studies. She also carries a double workload outside of class, as a teaching assistant at an elementary school and a CSUN academic mentor, passing on to fellow students the essential guidance she received to navigate college.

“I want to give back to the community that gave so much to me,” Coronado says.

Candelaria and Coronado reflect the aspirations of CSUN’s 39,000 students – and of the university itself. They are first-generation collegegoers, like 71% of fellow students; Latino/a, like more than half of the richly diverse student body; and from low-income families on a campus that has more Pell Grant recipients than any other public university in California. They are inspiring family members and friends to consider college. And, Candelaria and Coronado will enter the workforce equipped with skills that are critical to Southern California’s economic vitality.

“Higher education is the answer to much of what ails us,” CSUN President Erika D. Beck says. “We are the answer to what ails us.”

CSUN represents an educational model that is grounded in equity, committed to erasing racial-achievement gaps, and deeply integrated with the community it serves. CSUN’s medley of white and Black, Asian and Latino/a, Jewish and Armenian students is, in the words of the poet Maya Angelou, “a rainbow in the clouds.”

Set on 350 acres in the San Fernando Valley, a site where state-of-the-art facilities now seem to sprout as regularly as oranges once did, CSUN has long delivered inclusive academic excellence. Its nearly 400,000 alumni include students of humble origins who became leaders in business and entertainment, Pulitzer Prize winners, and even the first Second Gentleman of the United States, Doug Emhoff.

CSUN’s commitment to diversity extends to disabilities: Its Deaf-Studies expertise and campus support services have attracted hearing-impaired students for 60 years. One of them, actor Lauren Ridloff, made history as Marvel’s first deaf superhero in the 2021 film Eternals.

Most importantly, amid unaffordable private college tuition and widening income inequality, CSUN removes barriers to success for students from traditionally underserved communities and offers them a springboard into the middle class. CSUN ranks fourth nationwide in fostering social and economic mobility, based on a respected index that measures how well nearly 1,500 colleges educate students from low-income families and graduate them into well-paying jobs.

“This is an institution that has been values-driven and has done extraordinary work for a very long time before I ever set foot on this campus,” Beck, who joined CSUN in January 2021 after leading California State University Channel Islands, says. “We just need to tell our story, to amplify the understanding that what’s happening here is genuinely transformational.”

She wasted no time getting the message out, producing results that will help write the next chapter of CSUN’s story. Within months, philanthropist MacKenzie Scott and her husband, Dan Jewett, who widely support education for students from historically underserved communities, donated $40 million. It was the largest gift from a single donor in CSUN’s history.

Next, Apple made the second-biggest gift: $25 million, as part of a public-private partnership to develop an equity-centered technology hub that will provide state-of-the art labs for CSUN engineering and computer-science students and serve as a beacon for middle- and high-school underserved students to explore the wonders of STEM education and careers. Apple’s gift matched a $25-million allocation in the California state budget to build the facility, which CSUN hopes to open in 2024.

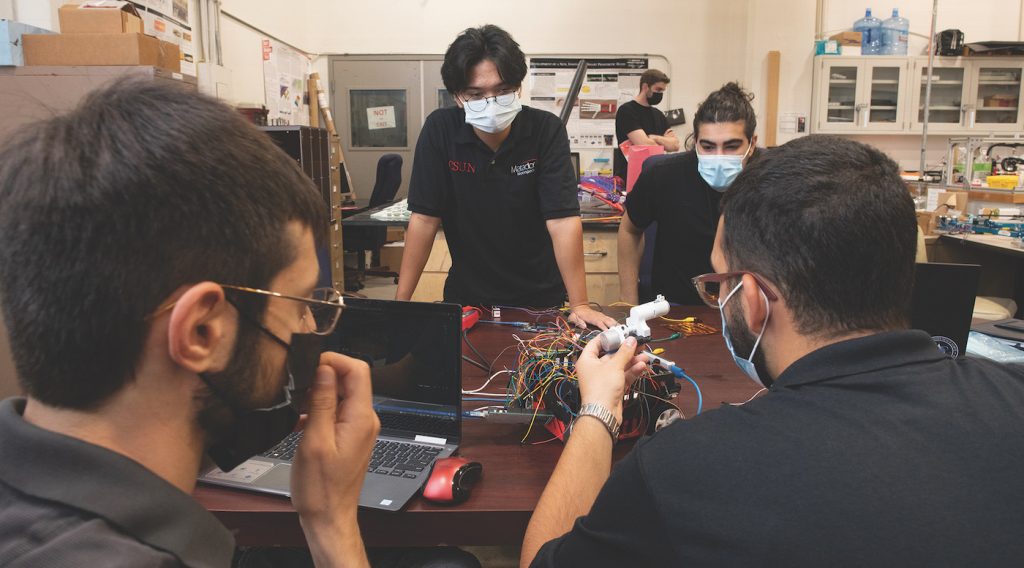

The Global Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) Equity Innovation Hub promises to be an immersive experience. A maker space will allow kids and their families to play with tools of technology, and curated displays will embed cultural symbolism and inspirational images of accomplished Latino/a and people of color in tech. Visitors will be able to enter labs to meet CSUN students and faculty and see their cutting-edge research in advanced robotics and other fields. The hub will also connect with students beyond Los Angeles through virtual programming, even before the building opens.

“So much of the Equity Innovation Hub is about helping young students and their families see themselves as the innovators and creators of the future and build a seamless pathway to college,” Beck says. “We lose too many students who never envision that possibility and never even make it to our doors.”

The Equity Innovation Hub encapsulates CSUN’s goals and challenges. It also illustrates the multiplier effect of collaboration, a core tenet of Beck’s educational and leadership philosophy.

Initially, CSUN alumnus Andrew Anagnost donated funds through Autodesk, the company he leads as President and CEO, to plan a “center of possibilities” in the College of Engineering and Computer Science. Encouraged by three Californian elected officials – each a Latino/a with an engineering degree and ties to the San Fernando Valley – CSU Chancellor Joseph Castro took the concept further to include STEM programming aimed at underserved groups across the CSU system. Governor Gavin Newsom backed the idea, and CSUN was chosen to host the hub and work in collaboration with the other 22 CSU campuses.

Apple’s vote of confidence added yet another dimension. Its offer of technology and design support on top of funding will enable CSUN to connect with HSIs around the country, positioning the university as a national leader in thought and practice for equity-centered STEM education. HSI is a designation under which an institution of higher education is eligible for federal funds if its undergraduate full-time enrollment has at least 25% Latino/a students and at least half of all degree-seeking students are low-income. For Beck, the Equity Innovation Hub is an opportunity for CSUN to forge a more cohesive identity and mission for this disparate group.

“As a leader who’s been really engaged in Hispanic-Serving Institutions, minority-serving institutions, and the national dialogue around student success and equity, what I have always wanted to be is that convener,” she says. “I want to connect with other leaders in common cause so that we can learn from each other.”

CSUN has been at the forefront of the drive for equitable higher education since before it was even named CSUN in 1972. Founded 14 years earlier as San Fernando Valley State College, like many American college campuses then, it had almost no students of color. Student activism in the ’60s made Northridge a hotbed of protests, as well as the birthplace of a program that has driven student success and social mobility ever since.

The Civil Rights Movement brought Black and Latino/a student groups together to demand greater diversity. In November 1968, Black Student Union members occupied the administration building until the college pledged, among other things, to boost the number of students and faculty of color and introduce ethnic studies. Afro-American Studies and Mexican-American Studies programs opened in 1969 and were among the first of their kinds in the country.

The social justice movement also led to a program known as the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP). EOP broadened admissions criteria for historically low-income and educationally disadvantaged students who were underrepresented at the university, to include consideration of their “high potential” and life circumstances, not just high-school grades and test scores. The Northridge campus was one of the first to have an EOP, which California established by legislative mandate in 1969. EOP is now in place at all 23 CSUs.

“There is not a program I know of that has been as enduring and as transformative as EOP,” says William Watkins, an early beneficiary in 1970 as a first-generation student from South Central Los Angeles. At CSUN, he was an award-winning Urban Studies major and the first African American elected student body president. He earned a doctorate in Education Leadership from UCLA and is currently vice president for Student Affairs and dean of students at CSUN.

EOP has served more than 30,000 CSUN students and evolved far beyond its origins as an admissions program. It offers academic advisement, peer and faculty mentoring, transitional programs, financial assistance, and even a program specifically for students in or exiting foster care. These services are designed to support, build resilience, and – perhaps most importantly for less-advantaged students to thrive – convey a sense of belonging.

“It has not only changed my life, it has also impacted my family’s,” Gustavo Sanchez, a junior majoring in Business Administration, says of EOP. His improbable path from a high schooler all too familiar with juvenile court to a successful first-generation student has encouraged relatives to follow, including a cousin who is at CSUN and a sister who plans to apply.

Such stories – not nostalgia or football boosterism – are why CSUN alumni are so passionate about their alma mater. David Nazarian, who attended CSUN shortly after immigrating from Iran, recalls that “I just wanted to get my degree, be done with it” and start a career. He added an MBA from USC, and only after he became a successful investor did Nazarian fully appreciate how important the classes, learning environment, and students at CSUN had been.

“On top of that, I saw that state universities would have a much bigger role in education going forward, and they were not getting enough attention or funding,” he says.

The Nazarian family has become one of CSUN’s top benefactors and fundraisers. The gleaming 1,700-seat performance hall on campus is named after Nazarian’s parents, Younes and Soraya, and known simply as The Soraya. The David Nazarian College of Business and Economics is the second-largest CSUN college, by number of students.

Nazarian invests his time as well as money, deriving pride from the work ethic of CSUN interns, entrepreneurship of students, and dynamism of the faculty.

“When I visit campus, I keep finding out about more great things that are going on under the radar,” he says.

Like the CSUN Innovation Incubator, whose director was invited by the U.S. State Department to South Africa to share his ideas with women and underserved populations. Or Bull Ring, a Shark Tank-like competition in which students from multiple colleges collaborate on business ideas for prize money. Such interdisciplinary projects are essential training for the workforce, as are programs tailored to emerging needs, like CSUN’s new Business Analytics major.

The fast-changing workplace means that “the most important piece is that we teach students to thrive in the context of ambiguity, by allowing them to solve problems in the way problems show up in the real world,” Beck says. “It is interdisciplinary, hands on, immersive. It is asking questions.”

The task is urgent. Society’s fundamental challenges – poverty, energy, climate change, and healthcare – are more complex than ever. California is the heart of the global innovation economy, yet if all of its colleges and universities keep producing graduates at the current rate, the state will face a deficit of more than 1.1 million jobs by 2030.

The CSU chancellor has set ambitious goals to boost graduation rates by 2025. CSUN is making gains in four-year and six-year graduation rates for first-time freshmen and it already surpasses the CSU target for transfer students to finish their studies in two years.

Beck brooks no illusions about the uphill battle to eliminate entrenched equity gaps. The difference between the six-year graduation rate for students from better-servedgroupsand those from traditionally underserved ones has narrowed to 8.4 percentage points. But beneath this aggregate number, Beck – an experimental psychologist devoted to scientific methodology and data – knows that the deficits are wider, even “deeply troubling,” among permutations of whites, Blacks, Latinos/as, low-income, first-generation, and other individual groups.

The traditional university model was built to serve largely middle-class students who were following a family tradition, not creating one. State universities like CSUN deserve a larger place in the dialogue about higher education, Beck says, because they graduate the most, and most diverse, students – the students of today and the backbone of the workforce of tomorrow. Declining government funding for public education, thus, makes outside resources all the more vital to the mission of advancing social mobility.

“What we do is a heavier lift,” says Beck, who sees CSUN as nothing less than the future of public higher education. “Investing in us is investing in a more equitable future and will reap enormous long-term benefits for the communities that we are so proud to serve.”

California State University, Northridge

www.csun.edu/foundation

(818) 677-4400

President: Nichole Ipach

Mission

California State University, Northridge exists to enable students to realize their educational goals. The University’s first priority is to promote the welfare and intellectual progress of students. To fulfill this mission, we design programs and activities to help students develop the academic competencies, professional skills, critical and creative abilities, and ethical values of learned persons who live in a democratic society, an interdependent world, and a technological age; we seek to foster a rigorous and contemporary understanding of the liberal arts, sciences, and professional disciplines, and we believe in the following values.

Begin to Build a Relationship

We know you care about where your money goes and how it is used. Connect with this organization’s leadership in order to begin to build this important relationship. Your email will be sent directly to this organization’s Director of Development and/or Executive Director.

Join California State University, Northridge in Its Bold and Inclusive Vision

Philanthropic investment in California State University, Northridge has a transformative impact. Recognized nationally as one of the top campuses for advancing the social mobility of its students, CSUN welcomes everyone who possesses a determination to make their mark in the world. They come from every background and rung of the socio-economic ladder. CSUN is where their talents are cultivated, where odds are overcome, and where aspirations, even those once seen as impossible, are fully realized.

In Southern California, CSUN answers an urgent call for an educated and diverse workforce, and in doing so, transforms lives, families, and communities. Support for CSUN drives local results with immediate impact and a significant return on investment.

Giving to CSUN is a contribution to a bold and inclusive vision, a commitment to some of the most comprehensive solutions to today’s most urgent challenges, and an investment in a brighter and more equitable future. For more information, visit https://engage.csun.edu.